In 2019 I embarked in my biggest DoD career challenge yet: I joined NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in a one-year assignment to guide the Engineering and Technology organization through a change management initiative. In this report, I will share how I used agile and design thinking to drive an organization through a 12-month change effort. In addition, I will also share the long-lasting effects the change initiative had on the organization and the many lessons I learned during my assignment. You will find this report insightful as it will give you a blueprint for organizational change.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) Engineering and Technology Directorate (ETD) [1] is a key contributor to a cross-organizational proposal development process (in this paper, referred as the GFSC process), where they provide engineering concepts and cost estimations for new projects. The GSFC process is a competitive process, where ETD provides feasible engineering concepts and cost estimations for proposals that will be submitted to NASA Headquarters for funding of new project opportunities. ETD’s engagement in the GSFC process takes from 12 to 18 months, with multiple proposals being worked simultaneously at different stages of the process. For years, ETD faced the challenges of providing timely engineering support to the GSFC process. This is a result of the competitive nature of the science environment, competing ETD internal and GSFC priorities, the nature of its evolving workforce where people change jobs based on their career goals and the limited resources of the organization. For too long the organization felt victim of the process and believed they could not affect changes to improve the GSFC process. Participation in the process was often perceived as a burden and not something everyone enjoyed.

As a Systems Engineer working in the Department of Defense (DoD) for 18 years, I had done cross- organizational process improvement but always within the boundaries of my DoD agency. However, in 2019, I was presented with my biggest challenge yet. I took a career broadening assignment to work at GSFC leading a change management effort for ETD in the context of the GSFC process. The change initiative was going to impact 1,200 employees approximately, and it was going to transform the organization’s role in the GSFC process.

2. Background

Prior my arrival, ETD leaders discussed the need to improve the organization’s role in the GSFC process. The ultimate goal was to increase the proposal win rate for GSFC and create more excitement among the ETD workforce to work proposal development. Upon my arrival, immediately, I was excited about the opportunity, but at the same time, I was worried about how I was going to learn a new organizational culture, their challenges and opportunities in the context of the GSFC process, identify solutions, provide recommendations, and begin implementation in only one year. Having done process improvement at a smaller scale in the past, I knew that I had a big challenge ahead of me and that I needed to move fast if I wanted to deliver significant results within the one-year timeframe. My first thought was to apply the techniques used in agile. We broke the change management effort in timeboxed phases:

- Assessment Phase—consisted of getting to know the organization, process, stakeholders, and beginning to understand the pains, gains, and opportunities in the GSFC process. Data gathering in this phase was focused on understanding the various roles that support the GSFC process and their specific pains, gains, and opportunities.

- Evaluation Phase—consisted of validating the initial pains, gains, opportunities to focus on specific problems areas to create a baseline of the GSFC process from the perspective of ETD, and lead the stakeholders (independent of the work role) from the problem space into the solutions space with the goal of creating a common vision for the organization. Outcome of the Evaluation Phase was the identification of solutions as luxuries, quick wins, high value, and long-term strategic initiatives which were input to the Recommendations Phase.

- Analysis Phase—analysis was done throughout Assessment and Evaluation to consolidate the data collected by common pains, gains, and potential solutions independent of the stakeholder roles to identify common themes and narrow down the scope of the effort.

- Recommendations Phase—recommendations were selected and prioritized from the quick wins and high value solutions as identified during the Evaluation Phase.

- Implementation Phase—this phase consisted of two parts: Planning and Execution, which provided the organization a roadmap for continuous improvement and for organizational change.

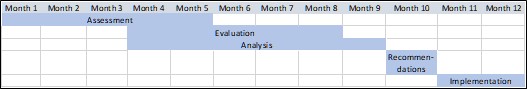

At the beginning of each phase, I set the objectives, timeline, and the expected outcome and benefits, which I communicated to senior leadership to keep them engaged in the process and to request their support if necessary. Some of the phases were done concurrently, and at the end of each phase, I presented the results to ETD senior leadership and mid-management to gather feedback and improve the approach based on the new learning. In each phase, I saw the organization transforming from skepticism about the change effort to embracing the changes and uniting to take control of their future. Figure 1 shows the timeline of the experience.

Figure 1 Timeline of the Experience

3. Your Story

3.1 The Assessment Phase (5 months)

Getting to Know Each Other: When I joined ETD, I did not know anything about the organization or the GSFC process. I did not know the people, and with the exception of my sponsor, people did not know why I was there. As a change agent coming from a completely different culture, I faced the challenges of learning the organization, the GSFC process, and the challenges encountered by the workforce in their daily work. I began the experience by learning the GSFC process and attending meetings with key stakeholders of the organization. With the support of my sponsor, I became versed in the process, and immediately gained access to leadership. At each meeting I attended, I briefed the objectives of the change initiative, and set expectations for the support that I needed from the leadership team. From that point forward, I started to become part of the organization: people knew why I was there and they started to talk about the change management effort.

Building Trust and Excitement for Change: Now it was time to dig deeper into the GSFC process to find the pains, gains, and opportunities the various stakeholders experienced. For this, I used the lean startup [3] approach. I conducted structured interviews with 21 stakeholders, focusing on the management aspect of the process. The interviews were a great method to have one-on-one interactions that made it easy to gather the information needed. Interviews created a safe environment that allowed me to get to know people at a more personal level. Interviews were 2 hours long, which showed the commitment of the stakeholders to the change initiative. I noticed that after the first 15-minutes of the interview, people started to feel more comfortable, and that is when they opened up and discussed the challenges, their frustrations with the process, and how they will like it to be improved. They also, came with great ideas to fix the problems. Before the interviews, stakeholders were skeptical of the value of the change effort, but that skepticism started to disappear during the face-to-face interviews. The fact that I came from another agency and I was not an internal stakeholder in the organization became an asset for me. People felt safe sharing their thoughts about the challenges faced by the organization. They did not perceive me as threat; instead, they saw me as the person who was there to help. Although interviews were long, I was very clear from the beginning that I only needed 2 hours of their time, and I would only follow up if I had specific questions. Therefore, people embraced the interviews and were happy to dedicate 2 hours of their busy schedule to meet with me. At this point people started to get excited about the change management effort.

Key to changing people’s mindset, was the fact that their voices were been heard and they realized that this was not a one-sided change effort initiated by management; instead individual input was taken into account for the multiple roles in the process. I used the mission model canvas [4] to capture the information collected during the interviews. By using the mission model canvas, I consolidated the information by work role to highlight specific pains, gains, and opportunities for each role, since they all interfaced at different stages of the GSFC process. The terms gains and pains were new to the organization. Introducing these new words brought a fresh perspective and created enthusiasm for learning and trying something new, thus creating more excitement for the effort. Moving forward, the words pains and gains became the trademark for the change effort when people referred about the initiative at the meetings.

Take the Burden Off Busy People: Key to the change effort was to not be disruptive of people’s work. People were already busy with mission work and they did not need additional work. So far, I had only gathered information from the people managing the process. As a next step, I needed to gather input from the people implementing the process: the systems engineering team. I knew that the engineering team was busy doing mission work, which was their priority. In addition, I had to gather feedback from more than 20 individuals. I knew that using the interview approach was not going to work; it was too slow. Instead, I conducted a design thinking workshop with the engineering team. First, I presented the proposal to senior leadership for their support. Then, I reached out to my DoD colleagues to plan and facilitate a 4-hour design thinking workshop.

Incremental Wins: Using the data collected during the interviews, my sponsor and I identified the top three common problem areas that we decided to use as the topics for the workshop. I setup the workshop by problem area and labeled each table by topic. This gave people the opportunity to work the areas they were most passionate about and helped frame the context for their participation in the workshop.

At the beginning of the workshop, people were curious about what we had planned for the day, and some were hesitant to share their perspectives of the GSFC process. As an icebreaker activity, we started the workshop using the Stakeholder Mapping [2] activity to get people thinking about the GSFC process and their interactions with the various stakeholders. This 10-minute activity, completely change the energy in the room. People started laughing and opened up about their experience with the process. Now ideas started to flow. For the workshop, I used various design thinking techniques [2]:

- Rose, Bud, Thorn to identify the positive, negative, and potentials in the various problem areas of the process;

- Affinity Clustering to identify patterns in the data;

- How Might We Statements to frame problem statements;

- Creative Matrix to generate a large number of ideas for the selected problem statements; and

- Concept Posters to capture the main points of the selected ideas.

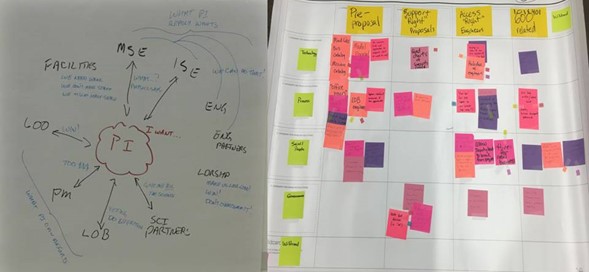

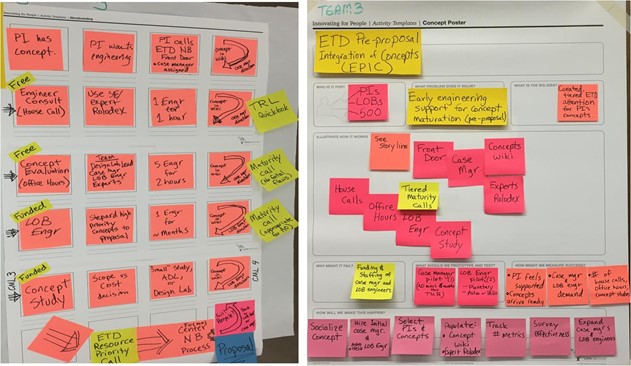

It turned out that by providing the teams an initial focus area and by letting them self-organize, the creation of ideas for solutions emerged in a more natural and creative way and they did not spend too much time over thinking potential solutions. Figures 2 and 3 show some of the work products developed during the workshop.

The design thinking workshop had a tremendous effect on the organization: the engineering team started to embrace the change effort because they became active contributors to the solutions. The teams were generating a lot of ideas and leveraging each other experiences. In addition, since the engineering team had so much fun with the activity, they provided their feedback to their peers and management, and the word spread across the organization about the change initiative. Now more people across ETD were curious about the change effort and wanted to get involved too. So now, both the engineering and management teams were fully engaged in the process. That was a win-win for everybody. I was able to get their full engagement and gather the information I needed, while they started to think about ways in which they could change their participation in the GSFC process. My confidence level went up. I felt like I was creating an impact on the organization. But at the same time, I also felt an immense pressure because the engineering team was counting on me to carry their voice to senior leadership and to ensure high value solutions (that work for them) were implemented as part of the change initiative.

During the assessment phase the combined teams identified a total of 77 gains, 155 pains, and 125 opportunities. A baseline of the GSFC process from the perspective of ETD was created showing their various points of engagement in the process and their respective gaps.

Figure 2 Design Thinking Workshop: Stakeholder Mapping and Creative Matrix

Figure 3 Design Thinking Workshop: Storyboard and Concept Poster

3.2 The Evaluation and Analysis Phases (6 months)

Creating a Common Goal: Evaluation and Analysis were done in parallel throughout the effort, and overlapped the Assessment Phase. Halfway into the Assessment Phase I already had a good idea of the top problem areas faced by the organization. Now I needed to lead the teams to focus on the potential solutions. During the evaluation phase, I presented to senior leadership and middle management the results from the workshops to gather their feedback and keep them engaged with the effort. In each meeting we had, the leadership team started to think more about things that were under their control to change so they could improve the GSFC process and how the organization felt about the process.

At this stage, I re-engaged with the management team in a design thinking workshop. By now, they had seen the results from the engineering team workshop. I used the same techniques I used with the engineering team, and conducted two 2-hour workshops with the management team to gather their perspectives for potential solutions.

During the workshops, I noticed that the management team, shifted from thinking about their individual roles in the process to focus on how they could facilitate the work of the engineering teams when working the GSFC process, and how to motivate and recognize them for their work. As a result of the workshop the team identified quick wins in which they could recognize the workforce in a timely manner and implement other incentives such as awards for people working the GSFC process; provide engineers more support in the form of mentoring; and sharing more information across projects and teams by creating repositories of information and implementing brown bag sessions or workshops. I noticed that the solutions drafted by both the engineering and management teams were in alignment. Now that both the engineering and management teams shared the same objectives, the next step was to merge the senior leadership team into the equation to ensure top-level support and commitment for implementation.

Learn and Pivot: Until now, things were going smoothly. I had people’s attention, they were engaged in the change initiative, and they were looking forward to the recommendations. It was time to add senior leadership into the mix. Up to this point, they were kept abreast of my work but they had been mostly passive stakeholders. To actively include senior leadership, I planned a larger design thinking workshop that included the engineering, management, and senior leadership teams. A total of 50 people participated on the activity. Since I did not have much time between the management workshop and the larger ETD workshop, I wanted to start the workshop with the concept posters created by the engineering team. I wanted each team to present their draft concepts for potential solutions as a starting point, and then have everybody refine the details for the implementation of the proposed solutions. I felt like I had a solid plan. However, when I reached out to the engineering team to get their buy-in, the teams did not agree on the approach. I could not get their support for the workshop. They did not feel comfortable showing a draft concept to senior leadership.

At that point, I realized that this was part of their organizational culture: there was a gap between the engineering team and the management/leadership teams. It was not that they did not want to support my efforts; it was that the engineering team was used to engaging leadership in formal settings and they would never show senior leadership a work product that was incomplete. I could not change that behavior that was already ingrained in their culture with only a few weeks before the workshop.

This was a setback. I needed the engineers to tell senior leadership their thoughts because they were the ones living the GSFC process every day. It took me about a week or more to recover and come up with a new plan. If I wanted the larger workshop to be a success for the organization, I had to pivot the approach to create a safe and comfortable environment for the engineering team so their voice was heard by senior leadership, but I also had to make the activity work in a manner that organizational roles and titles did not matter and everybody worked as a team.

Therefore, I changed my tactic. Instead of using a bottom-up approach, I sent read-ahead material to senior leadership showing the results from the engineering and management workshops, which included the preliminary proposed solutions and challenge areas. I met with all the mid-management team and key stakeholders to provide an overview of the change effort, the findings, and discuss expectations for the larger ETD workshop. Basically, I overloaded management and senior leadership with information and requested their support for the larger workshop, and made myself available to provide additional information if desired. I noticed that this approach worked well. Given that this was a very technical organization, they wanted to have as much information and data as possible before the workshop. That gave them time to formulate new ideas or build upon existing ideas before the event.

Lastly, I grouped the various problem areas in a list of the top 15 How Might We problem statements, and requested senior leadership prioritized the top six How Might We Statements that they wanted to explore in detailed during the workshop. Since all problems were interrelated, making improvements in one area would impact the other areas. Doing this, gave me a list of the top six problem areas for the combined teams to deep dive during the workshop, which ensured the workshop was in alignment with the organizational needs. Having senior leadership prioritize the list of problem statements was a key step to have them actively engage the change management initiative.

Make it Fun: The larger ETD workshop was an 8-hour activity. In order to motivate people to attend and not make it feel like a burden, we decided to call it a retreat. By calling the activity a retreat instead of a workshop, we sent the message to the workforce that this was a fun activity where all ETD stakeholders would participate, and was not perceived as 8 hours of work, but more as an opportunity for people to interact with their colleagues, see the friends they had not seen in a long time, and have some face time with senior leadership. Since it had been seven months since we started the change effort, I sent read ahead material to all workshop participants as a way to refresh their memories about the findings from the interviews and the previous workshops. For the workshop, I setup 6 groups and labeled each table with one of the How Might We Statements that were prioritized by senior leadership. When people walked into the room, they were allowed to self-organize. This provided them the opportunity to work the problem statements that resonated more with them given their own experience with the process and their ideas for solutions. The initial 15 minutes of the workshop were dedicated to discuss each How Might Statements. Doing this allowed senior leadership to engage the workforce and provide their perspective about the importance of fixing each problem. This initial activity helped set the stage for the workshop and provided individuals the opportunity to move to another group if desired. By allowing the teams to self-organize, each group had a good balance of senior leadership, mid-management, and engineers, which allowed capturing the combined perspectives of the three main stakeholder groups.

Teams had their problem statements and it was time to deep dive into exploring ideas for solutions using the Creative Matrix. Since the engineering and management teams had already used the Creative Matrix in their respective workshops, they knew what to do and what to expect. I saw how leaders emerged at each table, independent of their work role or place in the organization, and noticed how they began to lead their peers into the activities without much guidance from me or my DoD peers who were helping facilitate the workshop. They were having deep discussions at each table, everybody was expressing opinions, and people were receptive and respectful of their peer’s ideas. The room was full of positive energy. People were fully engaged in the discussion of ideas for solutions. In addition they were making jokes, and thinking about long-term solutions. All voices were heard and accounted for when the teams put down ideas in the creative matrix.

I observed how the dynamics of the teams changed. People felt comfortable sharing their ideas, even if they were out of the box ideas. Some teams wrote down solutions that had dependencies on other teams, so they passed them as “requirements” for the other teams; thus showing the interrelationship of solutions.

During the workshop, I observed how organizational silos started to break: engineers were sharing their perspectives with management and senior leadership, and some of them were leading their teams through the workshop activities. All teams were collaborating towards a common vision.

At this moment I realized that this was a far better approach than my original plan of having the engineers brief their concept posters. Instead of having one team telling the others what they wanted, everybody was participating in the process of creating solutions instead of being one-sided. Until now, I had not realized that if I had started the workshop with the engineering team presenting their proposed solutions, I was putting them in a position where the other teams did not feel included and that will have a created a contentious environment for the workshop. Now I was so glad (and relieved) that the engineering team overruled my initial plan. In this one-hour activity, the teams identified 213 ideas for solutions. Each team was then asked to identify the top 10 ideas that they thought were most feasible to implement independent of its complexity. This was not a prioritization exercise; instead, it was intended to create a “repository” of ideas for potential solutions that the organization could refer back in the future for additional process improvement efforts.

The next step was for each team to use the Impact/Benefit Assessment Matrix to categorize each potential solution as luxuries (not worth investing time), quick wins, high value, and long term strategic efforts. After binning their top 10 ideas in each category, teams were asked to select only 1 idea from the quick win or high value quadrants, which they used during the rest of the workshop. The Impact/Benefit Assessment helped the teams visualize the relationships between the various potential solutions, and provided a roadmap of where to start the changes so they could see immediate results, but with a long-term strategic goal in mind.

Each team created Storyboards and Concept Posters for their top idea to describe how the solution will work, what was needed to realize the solutions, risks, benefits, and a timeline. During this part of the workshop, I noticed how the management, engineering, and senior leadership teams united to create a new vision of the GSFC process, where all of them were represented. Ideas were flowing, and they even discussed creating new work roles, adding steps to the GSFC process, and engaging other organizations external to ETD so they could change their part of the process to be more in tune with ETD proposed changes. This was a transformation of their mindset: now instead of feeling that they could not affect changes to the corporate GSFC process, they were seeing themselves as the leaders of a larger change effort impacting the entire corporate process. That was a big step.

As outcomes of the workshop, the organization identified 60 potential solutions binned by their level of impact and importance, and they created detailed plans that will serve as a guide for the implementation of selected solutions. At the end of the day, people where happy to be part of the activity and they continued talking about all the things that could be done to make the change happen. Some team members expressed that they wanted to continue being involved during the implementation phase.

This was a pivotal moment for everyone: the organization took ownership of the change effort, and my role started to transform from the person leading the effort to a support role.

Seek Allies: During the workshop, we invited key senior leaders from other organizations to observe. Although they knew the goal of the change effort, being able to watch what was happening during the workshop opened their eyes. They were able to see how their organizations could make changes to their piece of the GSFC process to make things more manageable for everyone. Having external stakeholders observe the workshop, only if it was for 10 minutes, was an excellent way to gain support from those organizations. They were looking forward to see the recommendations and to partner to find ways to help. In addition, they expressed their interest in doing similar design thinking workshops internally in their organizations to help with process improvement.

3.3 The Recommendations Phase (1 month)

The Recommendations Phase was straightforward. The teams had already done the hard work during the workshop. The top six ideas for potential solutions were provided to leadership for review and concurrence. Due to the limited resources and people working other activities, leadership combined some of the recommendations to make it more manageable. At the end, we finished with three recommendations for implementation. Also as part of this phase, I requested leadership to identify leads for each of the recommendations. These were going to be the champions who will continue the change effort after my departure. The goal was to provide accountability during the implementation phase. In order to select the team leads that will be responsible for implementation, management asked the people who self-identified as leads during the ETD workshop if they were interested in continuing to support the effort through implementation. By using this approach, leadership identified team leads and team members for each of the recommendations that were going to be implemented. Throughout implementation, the champions were to be accountable to the organization for implementing the recommendations. My next step was to work with the team leads to refine their respective recommendations and create implementation plans with a clear roadmap for execution.

3.4 The Implementation Phase (2 months)

The Implementation Phase consisted of two parts: Planning and Execution. During Planning, I met with the team leads to refine the scope of the recommendation and create strategic plans. Strategic plans captured the prioritized goals, milestones, and key results for each recommendation. From the strategic goals, I worked with the team leads to create implementation plans. The implementation plans provided more details about the specific tasks required to achieve the desired goals and outcomes.

During Execution, the team leads identified other team members who will help implement individual tasks. At this stage, we reached out to the other participants of the workshop. This provided another opportunity to blend the management, engineering, and leadership teams across the organization. The implementation teams represented multiple work roles and divisions within the organization.

By then, I was running out of time: my assignment was about to end. To make sure they had a path moving forward, I created a backlog and roadmap containing the strategic plans and implementation plans using Office 365 Teams and Planner tools, so I could leave them a place to collaborate and monitor their progress. I also provided them a process for regular reviews and update of progress during implementation.

Early in the implementation phase, they realized that they could not continue depending on me—I was leaving in a matter of weeks—and that it was their responsibility to make the changes if they wanted to see improvements in the process. They were aware it was going to be a slow change process, but now they had a clear roadmap moving forward, and they knew that it was up to them to make the changes happen. That is when I observed ETDs full transformation: they changed their mindset from talking about the pains of the GSFC process to become the champions and leaders of change; from working in independent pockets of the organization to collaborating as a unit towards a common vision; and they were eager to create a new future for the organization. A year later after my work in ETD was completed; I was informed about how my work created the foundation for a larger change initiative called Digital Transformation. Changing the mindset of the people and taking the steps to improve ETDs participation in the GSFC process was the first move to implement changes at scale.

4. Lessons Learned

There were so many takeaways from the experience. I grew both as a person and as a professional during my assignment, built a network outside my DoD organization, and gained the confidence to get out of my comfort zone and create a long-lasting impact in an organization that was previously unknown to me. These are assets that I will continue using throughout my career. My key takeaways are:

- The biggest lesson I learned is to always listen to the stakeholders; to validate their needs; make it easy for them to share; and take actions that addressed their needs and concerns. In addition, by providing opportunities to senior leadership for prioritizing problem statements and recommendations, the organizational needs were addressed, thus providing a path for success. Also since ETD addressed the people first they were able to influence larger changes that are being embraced by the stakeholders.

- A successful change effort needs strong champions and strong leads who will continue leading the way past the initial changes. ETD champions and leads had many years of experience in the organization, were passionate about their work and improving conditions, were recognized subject matter experts, and had a good understanding of the organization and the process. As a result, they were comfortable leveraging their network at any time to influence changes to create the new vision for the organization.

- A change effort needs branding. Introducing new terms and techniques to the organization that were unique to the change effort, such as pains and gains, created excitement for trying new things, made it fun, and became the trademark for the effort.

- Leading change in increments helped to gradually lead people to create and share a common new vision. The timeboxed phases with clearly defined outcomes helped stakeholders see themselves in the change initiative and how they could influence change. Bringing everybody together in a large workshop wrapped up all the collective solutions to create a common path forward.

- As the change agent, it was very important to get buy-in from the organization. This meant not putting the burden on the stakeholders. In the initial phases of the change effort, I took most of the load to ensure the effort kept moving and roadblocks were removed on time. Later during the effort, the organization took full ownership, and I was there only to facilitate when needed.

A change initiative does not stop with the recommendations. The creation of implementation plans and roadmaps provided accountability and a clear path for implementation. Without an implementation plan, people may not know where to start or may not feel compelled to start, but having a roadmap for implementation provides tangible results and outcomes, and keeps the energy going.

5. Acknowledgements

First, I want to thank my sponsor at NASA GSFC Dr. David Richardson; his mentoring and guidance helped me quickly acclimate to a new organization and kept the momentum going for the change initiative. Thanks for trusting me with the change effort and for your support. Thanks to my DoD colleagues for helping me plan and facilitate the design thinking workshops. I could not have done it without you! I am grateful for my DoD supervisors and mentors who give me the opportunity of broadening my career by doing this special assignment. A special thanks to my shepherd David Dikel for helping me bring this experience report to life; and to Rebecca Wirfs-Brock and David Kane for the opportunity of publishing this report in Agile 2021. Finally, I am thankful for my husband and my son for being by biggest supporters in all of my endeavors.

REFERENCES

[1] Website: https://etd.gsfc.nasa.gov/ [Accessed March 2021]

[2] LUMA Institute for Design Thinking. Website: http://luma-institute.com. [Accessed January 2021]

[3] The Lean Startup Methodology. Website: http://theleanstartup.com/principles [Accessed February 2021]

[4] Mission Model Canvas- An Adapted Business Model Canvas for Mission-Driven Organizations https://steveblank.com/2016/02/23/the-mission-model-canvas-an-adapted-business-model-canvas-for-mission-driven-organizations/ [Accessed February 2021]